This week: Granada, one of my favorite places to eat and drink. Berenjena frita—fried eggplant, thin slices both tender and crispy, drizzled in molasses. Cogollos a la cordobesa—hearts of romaine tossed with crunchy little bits of fried garlic and the olive oil they rode in on: warm and earthy, cool and fresh. All at once. Both of these dishes to be served immediately after preparation, maybe as prelude to calamar a la plancha—grilled squid, w/garlic and lemon—all it needs, if done right. Accompanied by my stand-by favorite, a tinto de Ribera (del Duero–a region less known in the U.S. than the Rioja for its fruit of the vine; Ribera reds are lighter, happier to hang w/fish, and I far prefer them). Croquetas—croquettes, Spain’s most divine comfort food; tonight’s were mushroom, or spinach, or jamón de bellota. Croquetas put hushpuppies to shame, shamed as I am to admit that, Southern girl that I am.

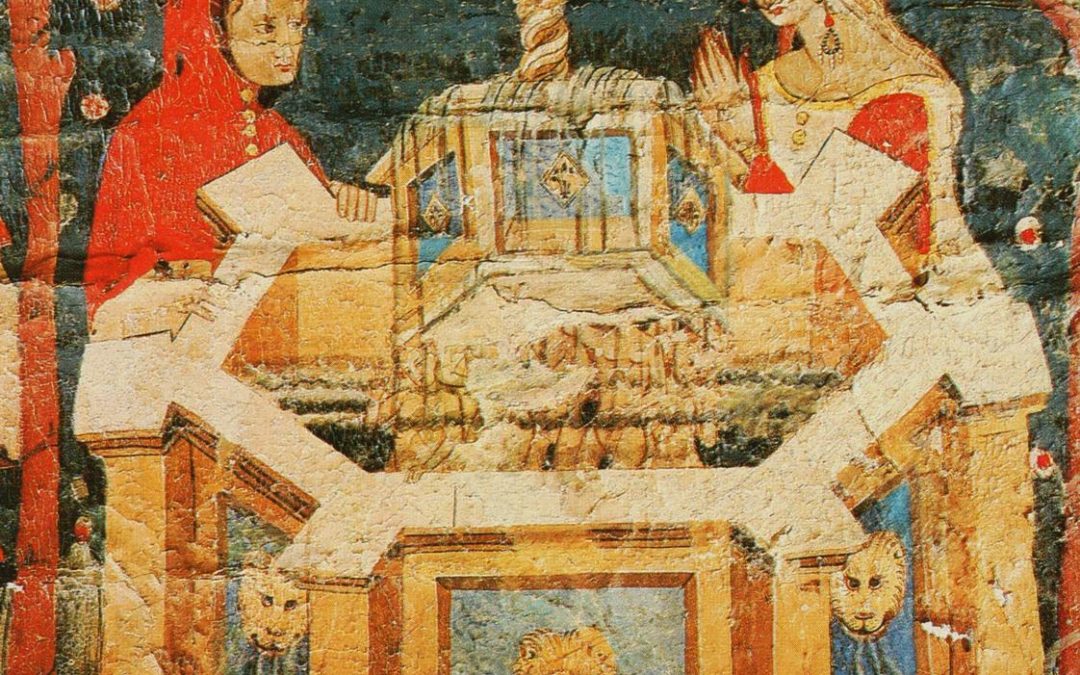

The idea was to make this a post all about food. I even spent the week snapping food porn (a number of which shots have made their way onto Instagram, or will do so imminently). Moments not spent ingesting the heavenly culinary creations that inspired the food porn, however, have been dedicated to wrapping up a study of the 14th-century Nasrid palace popularly known as Daralhorra—a Hispanized version of the Arabic for “palace of the free (or noble) woman”—located in the Albaicín, just across the Darro River from the better-known Alhambra.

My colleagues and I have arrived at the conclusion that Daralhorra did not belong, as is widely believed, to `Aisha, mother of the final sultan of Granada (Boabdil, the lily-livered one who handed the keys of the kingdom to Fernando and Isabel, los Reyes Católicos, yep, that’s the one, fine to hate him).

Rather, archival sources indicate that it figured among the real-estate holdings of Boabdil’s father’s second wife, al-Zahrā’, the Zoraya of Spanish language and legend. Before Zoraya was his wife, she was Muley Hacén’s concubine, and before that, she was the servant who swept his bedchamber. Before someone handed her a broom and told her to get to work, she was a terrified twelve-year-old girl, snatched up onto a horse by Nasrid raiders galloping through the outskirts of her town, where she’d gone with several other children to draw water from a well.

Before someone at the Nasrid court named her Zoraya, her mother called her Isabel. Al-Zahrā’ can be loosely translated as “splendorous,” which she, by all accounts, was–beauty can be a double-edged sword.

Isabel/Zahrā’/Zoraya bore the Sultan of Granada two sons, who came very close to inheriting the Nasrid throne. She lived by his side for decades. Once they were wed, he wouldn’t rest until his subjects recognized her, rather than his repudiated wife, as his rightful consort.

And yet, she must have been in her very early teens the first time she was brought to the sultan’s bed. Though there are elements of her story that smack of medieval romance—the well, the palace, the silks, the jewels—once those are peeled back we’re left with a vulnerable young girl, in a subservient relationship to a very powerful man, who had little if any choice about the ways in which her body would be used.

My imaginings of Isabel, this week, keep getting interfered with by images of Beverly Young Nelson, the latest of Roy Moore’s victims to come forward. Wiping tears, standing before microphones to take questions from the press, obviously middle-aged, perhaps she doesn’t touch hearts the way a very young girl might. She’s old enough to take care of herself—I even caught myself thinking that.

But she, like Zoraya, was a teen-aged girl—a waitress rather than a chamber maid—when Roy Moore, a regular at the Alabama restaurant (which did not serve cogollos a la cordobesa, maybe not even salad) where she worked–for ridiculously tiny paychecks and tips she had to smile for–grabbed her breasts with one hand, her neck with the other. The same age I was, more or less, when the manager of a fast food restaurant in Tennessee–where I, along w/other female employees, wore a short, tight red dress with a candy-striped apron—announced, one fine day, that he didn’t keep me on salad bar because I was good at it (I was, as I have been at all my jobs). He kept me on salad bar because he liked to watch me bend over. He was standing too close, I could smell his breath. I took a step back, away from him, away from the open walk-in door.

Women in the “hospitality industry,” as it used to be so quaintly called, deal with this crap alllllllllllll the time. And the hot ones get it worse. As Leigh Corfman and Beverly Young well know–both were clearly very attractive in their youth; one is still so as a mature woman (haven’t seen a photograph of the mature Leigh Corfman; like I say, beauty is a double-edged sword, maybe she’d prefer to be ugly)–a lifetime of said crap ends up messing with your head. Zoraya lived to a ripe old age, part of it in exile and in penury–her ‘husband’ was her senior by many, many years, and when he died, the vultures circled eagerly. Wish I could brew her a Turkisn (or Andalusi) coffee and pick her brain…

Meanwhile, in the news, these stories just keep coming—that’s a good thing, right? Sunlight is the best disinfectant?—and I can’t look away (Al Franken, yup, #himtoo: much as I wish this were a Purely Partisan Problem, it ain’t. Even the ones who are okay with a woman’s right to choose [abortion] occasionally show their true colors, tho’ at least they have the decency to own up and say sorry, my bad). This week, they’re messing not only with my head, but with my historical objectivity, as I try to take a scholar’s attitude toward Zoraya and her hard-won palace. Maybe that’s a good thing too.